- Home

- Cornelia Funke

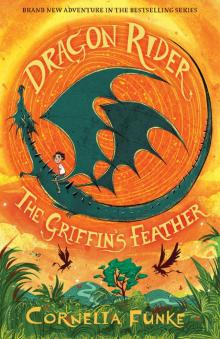

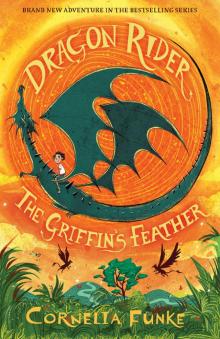

The Griffin's Feather Page 8

The Griffin's Feather Read online

Page 8

Ben was just turning around – very quickly so that the dragon wouldn’t see his suspiciously moist eyes – when Firedrake called him back once more.

‘I have a present for you,’ he said as he stretched his wings.

‘And I’m telling you again, this is not a good idea!’ Sorrel shouted down from his back.

The dragon ignored her.

‘One of the stone-dwarves who helped us to free the petrified dragons two years ago…’ he began.

‘… and we all know what stupid idiots stone-dwarves are!’ muttered Sorrel.

Firedrake silenced her with a stern glance.

‘One of the stone-dwarves,’ he began again, ‘claims that in the old days all dragons gave their riders one of their scales so that they would sense when they were in danger. A dragon rider had only to close his hand around the scale, and his dragon felt what he was feeling: joy, fear…’

‘… and as a result the dragons went around with great big gaps in their scales!’ growled Sorrel.

By this time she was fonder of Ben than she would admit to herself, but her first concern was always for Firedrake. After all, she had spent half her life with him before the boy came on the scene. Without anyone ever talking about giving scales away or similar stupid notions. And without all that never-ending flying from one end of the earth to the other. Brownies hate change. In Sorrel’s experience, however, there was nothing that human beings liked better. What made it all more of a nuisance was that her dragon had picked a human being as his best friend. Best friend after her, of course.

‘Sorrel’s right,’ said Ben (yes, he really was one of the good humans). ‘Getting rid of a scale really doesn’t sound great.’

But Firedrake was already plucking it off his breast.

‘It’ll grow back,’ he said, as Ben stared anxiously at the dark place left in his scaly coat.

‘Suppose it doesn’t?’ snapped Sorrel.

Behind them, Hothbrodd was blowing the horn that he had designed to look like the Vikings’ signal horns. It was a strange sound in the mountains of western India.

‘Coming!’ called Ben, as Firedrake let the scale drop into his hand.

It was almost as cool and round as a coin – and it reminded Ben of another scale: Nettlebrand’s golden scale, which had helped him to defeat the enemy of all dragons.

He closed his fingers around Firedrake’s gift. It might help with the longing he felt for his friend – who knew?

‘Can you sense anything?’ he asked the dragon.

‘The sorrow of saying goodbye,’ replied Firedrake. ‘But we neither of us need a scale to know about each other, do we? Use it any time you need help. Promise me! Now, Hothbrodd is really getting impatient!’

The troll was standing in front of his aircraft, waving to Ben with both arms.

Ben tucked the dragon’s scale into his jacket pocket, and put his arms around Firedrake’s neck one last time.

‘I wish I could give you something in return,’ he said in a husky voice. ‘But humans don’t have any scales, unfortunately.’

Then he turned around and ran towards Hothbrodd.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Trouble in MÍMAMEIĐR

It’s hard being left behind. […]

It’s hard to be the one who stays.

Audrey Niffenegger, The Time Traveler’s Wife

Guinevere was not the kind of girl who had always dreamed of riding a horse of her own. If your friends include grasselves and impets, and you’re used to nursing mermaids injured by ships’ propellers back to health in the bathtub, horses are not necessarily the most exciting living creatures in your world. Of course, Guinevere had met many fabulous members of the horse family. At the age of eight, she had ridden her first kelpie, and when she was ten she had saved three elf-horses from a swarm of wild wasps. Sea-foam horses, wind-mares, cloud-stallions – Guinevere knew them all. But none of those beings who galloped on hooves had ever enchanted her more than elves, impets or hedgehog-men. Until Ànemos came to MÍMAMEIĐR.

The task that Firedrake and Barnabas had given the Pegasus took his mind off his sorrows a little. He was to be found regularly on the banks of the fjord, settling quarrels between fossegrims and nymphs, or mustard-midgets and beavers. He met foxes, weasels and wolves on the borders of MÍMAMEIĐR, and asked them to go in search of some other hunting ground; he flew above caves, huts and houses at twilight with the mist-ravens to deter predatory birds who might have snatched an impet for a snack; and by scraping his hooves behind the stables he made water spring up from the earth that healed not only wounds, but weariness and homesickness. The new brook was soon attracting fabulous creatures both large and small. But the miracle-working water could do nothing to dispel the sadness that surrounded the Pegasus himself like a dark cloud.

Everyone in MÍMAMEIĐR knew that Ànemos almost never went into the stable where swans and geese were keeping his orphaned eggs warm. It was almost as if the Pegasus were trying to forget that they existed at all. Why set your heart on something that’s as good as lost already – was that the way he was thinking? Guinevere asked herself that question when she saw Ànemos, with his head sadly bent, standing in the meadows behind the stable where the shining shells of his unborn children lay.

The feathered inhabitants of MÍMAMEIĐR stood in line to warm the nest. On Undset’s instructions, Guinevere took the temperature of the eggs every hour, and she could soon report that (much to the annoyance of the swans) wild geese kept the nest warm best. She drew up a calendar with the days still to go until the eggs had to grow – and regretted it as soon as she hung the calendar on the stable door. Guinevere had left space to record every observation she made of the eggs. Unfortunately that showed, only too clearly, how little time there was left. Seven dates were still empty. Seven white squares filled only with the desperate hope that Ben and her father would be back in time with the feather of a griffin, and that feather would make not just gold or stone but also Pegasus eggs grow.

Guinevere had just been feeding the two geese sitting on the nest at present when Vita took her aside, and asked if she had seen Ànemos eating.

Guinevere could only shake her head. ‘The mist-ravens have tried making friends with him,’ she said. ‘But he keeps himself to himself, even when he’s flying on their rounds with them. He hardly says anything, and he isn’t eating or sleeping. I’m really worried.’

‘With good reason, I’m afraid,’ said her mother.

Guinevere had seldom seen Vita so depressed before. The death of the Pegasus mare had grieved her deeply; she shared the suffering of Ànemos, and hated herself for being able to offer him so little help.

‘I’m going to ask the mist-ravens to find an old friend of mine,’ she said. ‘Maybe she can get through to Ànemos in his time of trouble. Her herd wasn’t far from here when I last heard from her.’

‘Herd?’ asked Guinevere.

‘Yes, Raskervint is a centaur,’ replied Vita. ‘They’re more like Pegasi than people think. Though of course that doesn’t mean she can help us. However, there’s always hope, and often that’s all we have, right?’

Yes, that was only too true. Another reason to hope was that they hadn’t heard from Ben and her father for two days, because Hothbrodd, like all trolls, disrupted radio communication. They must be doing fine, she was sure of that! And they would find the feather. And get back here in time. She hoped. Guinevere only wished there was more she could have done. By now, even finding the feather of a griffin seemed easier than this helpless waiting.

‘I didn’t know you were friends with a centaur,’ she said to her mother.

‘Why does that surprise you, Guinevere Greenbloom?’ retorted Vita. ‘When your father and I met, we had a bet to see which of us had met more fabulous creatures. And who do you think won? Although,’ she added with a smile, ‘Barnabas has caught up with me now.’

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Me-Rah Tells Her Story

‘Animals don’t

behave like men,’ he said. ‘If they have

to fight, they fight; and if they have to kill they kill.

But they don’t sit down and set their wits to work

to devise ways of spoiling other creatures’ lives and

hurting them. They have dignity and animality.’

Richard Adams, Watership Down

This world looks rather different to all its inhabitants. To Me-Rah, it consisted of leaves, fruits, seeds and clouds, of snakes who stole eggs, apes and pine martens. She could tell Hothbrodd that it would take them six days to fly over the island that was her home from east to west, and three days to cross it from south to north, but of course she did not give animals and plants, or the four points of the compass, their human names. She spoke of where the sun is born from the sea, and where it goes to its nest in the mountains in the evening, she told them about long and short shadows, about the place where the swimming toads with horny shells bred (Twigleg translated those as turtles), or the direction in which the scentless wax flowers (orchids, Twigleg translated) turned their blossoms at noon.

Me-Rah knew a very great deal about her world.

‘Because she’s still at one with it,’ Barnabas whispered to Ben after the homesick chattering lory had spent over an hour describing her island, with longing in her husky voice (and a slight Indonesian accent). ‘It’s a sense for which I deeply envy every animal. I think I’d like to be reborn as a parrot. Although not in a cage and with clipped wings.’

Me-Rah’s wing feathers had grown back since her escape, but she still couldn’t fly with as much certainty and stamina as before her imprisonment. Ben hoped very much that wouldn’t endanger her in the wild. Hothbrodd was still watching Me-Rah with the utmost suspicion, and jumped every time she turned her beak to gnaw the tree-perch he had made for her. Lola, on the other hand, was soon talking shop with Me-Rah about upwinds and turbulence, maybe because they were both among the smaller denizens of the world.

Me-Rah assured them that there were no human settlements on her island home. The birdcatchers whose victim she herself had been came in boats, like the hunters in pursuit of monkeys, wildcats, or sun bears. But it was very unusual for any of them to reach the heart of the island.

‘For fear of the lion-birds, I suppose?’ commented Barnabas.

‘Oh no, fully-grown Greenbloom!’ replied Me-Rah. (She called Ben ‘still-growing Greenbloom’.) ‘The lion-birds even do business with the poachers.’

That was certainly a surprise.

‘May I ask what kind of business?’ asked Barnabas.

‘They allow only people who pay them to hunt in their kingdom, as they call it,’ squawked Me-Rah. ‘They eat the others.’

Twigleg cast Ben a horrified glance, but Ben himself seemed to like Me-Rah’s information.

‘They eat poachers! So what?’ was all he said. ‘I sometimes wish all animals would do the same! Anyway, we’re not poachers, so where’s the problem?’

Twigleg thought that was a very optimistic attitude.

‘May… may I ask how many lion-birds we’re talking about, Me-Rah?’ he asked in what he considered an admirably casual tone of voice.

Me-Rah lapsed into her dialect of Parrot.

‘Enough to turn the day into night,’ Twigleg translated. It sounded extremely disturbing.

Me-Rah chattered something else even faster.

‘And they have many servants? What kind of servants?’

Even Ben could tell that Me-Rah was enumerating many different creatures. Twigleg didn’t go to the trouble of translating the entire list. It sounded as if Me-Rah’s whole island was in the service of the griffins!

‘Master,’ he said in a voice he had difficulty in controlling, ‘I think it’s about time we weighed up the ratio of risks to advantages on this expedition!’

‘My dear Twigleg, we only have to let the griffins know we come with peaceful intentions!’ Barnabas reassured the homunculus. ‘As you’ve heard, they do business with poachers. So why not with us?’

Twigleg thought this line of argument as unconvincing as Ben’s, but he stopped himself reminding them of the poachers who had been eaten.

‘All this is extraordinarily helpful, Me-Rah!’ said Barnabas. ‘I’m so glad you’ve already said you’re prepared to help us! Could you maybe look at our map and say which of the islands drawn on it is most like the shape of your own home?’

In some confusion, the parrot looked at the patches of green that Gilbert Greytail had painted on the apparently endless surface of the sea surrounding the islands of Indonesia. Finally she pecked the largest of them.

‘So there we are!’ cried Barnabas, but he fell silent when Me-Rah pecked five more islands. She obviously thought that Gilbert’s cartography was edible.

‘Well, I suppose that would have been rather too easy!’ murmured Barnabas, making a brave effort to hide his disappointment. ‘Maybe there’s another way to approach it. Judging by the fruits and animals that Me-Rah has described, our destination must be in the north-eastern climatic zone of Indonesia. So let’s begin here.’ And he put his finger on the most eastern island that Gilbert had drawn. ‘And then we’ll reconnoitre all the uninhabited islands within a radius of fifty miles. If that doesn’t bring any results, we’ll extend our search to a radius of a hundred miles, and so on and so on…’

He was trying hard to sound optimistic, but it wasn’t difficult to see that he was worried. That morning, they had finally been in touch with Vita and Guinevere, and had heard that keeping the eggs warm presented no problems, but Ànemos still wasn’t eating.

Ben looked down at the endless sea over which they had been flying for hours, and tried to think only of the Pegasi. He summoned up his memory of the despair in the eyes of Ànemos, and took the photo of the eggs that Guinevere had given him out of his pocket, but all he saw in his mind’s eye was the dragon. His heart was still so heavy with longing for Firedrake that it wouldn’t have surprised Ben if the weight of it had brought Hothbrodd’s plane down. What was a dragon rider without his dragon?

He sighed, sensing Twigleg’s sympathetic look turned on him. As usual when they were flying, the homunculus was sitting on Ben’s knee, with a belt around his stick-thin body and attached to Ben’s own seat belt – not the safest of methods. In turbulence, Ben had often had to pluck Twigleg down from the air, but the homunculus preferred to be close to his master so high above the ground, although Hothbrodd had made him a seat specially for someone his own size.

‘You’ll soon be seeing Firedrake again, master!’ he said encouragingly.

Ben could hide his troubles even from Barnabas more easily than from the homunculus. Barnabas had so many things to worry about, but Twigleg had made Ben the centre of his world, and shared every one of his feelings and anxieties. Ben would very much have liked to tell him about his decision to join the dragon when this mission was over, but it would have felt like treachery to share his plan with the homunculus and not Barnabas.

As usual, Twigleg had his notebook with him, and he had written down everything Me-Rah said about her island. It was impossible for human tongues to pronounce the name that the chattering lory gave it, but she also knew its human name: Pulau Bulu, the Feathered Island. Twigleg had noted, No active volcano!, adding several more exclamation marks. In the course of his research, he had found out that volcanic eruptions were as common in Indonesia as the Northern Lights in Norway.

‘Right. If I’ve translated Me-Rah’s descriptions correctly, there are orchid trees and umbrella trees on her island, teak and golden rain, elephant apples, melati, orchids, and the carnivorous Rafflesia arnoldii, or corpse flower.’ The homunculus lowered his pen. ‘That means we can already rule out several groups of islands.’ He looked enquiringly at the parrot. ‘Can you describe any other plants that grow on Pulau Bulu? The rarer the better!’

Me-Rah cleaned her red breast feathers. She already looked less rumpled than before. Barnabas had fed her crushed oyster shells, and

given her a dish of water to bathe in, even though Hothbrodd had told him disapprovingly that water was not a good idea on board an aircraft.

‘Did I mention the Singing Flowers?’ Me-Rah plucked a feather that always insisted on sticking out at an angle away from her wing.

Barnabas raised his head.

‘The seeds are as large as nuts, and they taste as sweet as coconut flesh, but you have to get right into the cup of the flower to eat them,’ the parrot went on. ‘That can be difficult, because the scent of a Singing Flower can make you unconscious within seconds, and if you don’t get out again quickly enough, the flower will close and digest you, feathers and bones and all.’

Shuddering, Me-Rah fluffed herself up, but Barnabas let out such a cry of delight that Hothbrodd looped the loop in alarm, and Me-Rah flew down under the seat.

‘Excuse my loss of self-control, honoured and ever-helpful Me-Rah.’ Barnabas knelt down between the seats and remorsefully held out the palm of his hand to the parrot. ‘But singing flowers! This is fantastic!’

Hesitantly, Me-Rah climbed up on his hand – and cooed in alarm when, in his gratitude, Barnabas kissed her on the beak.

‘I’m sure they must be the extremely rare Lupina cantanda, also known as the Singing Plant-Wolf !’ he announced triumphantly. ‘As far as I know, it occurs only on this island group!’

Inkdeath

Inkdeath Inkheart

Inkheart Ghost Knight

Ghost Knight Inkspell

Inkspell The Golden Yarn

The Golden Yarn Fearless

Fearless The Thief Lord

The Thief Lord The Griffin's Feather

The Griffin's Feather Igraine the Brave

Igraine the Brave Reckless

Reckless When Santa Fell to Earth

When Santa Fell to Earth Dragon Rider

Dragon Rider Living Shadows

Living Shadows Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale

Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale The MirrorWorld Anthology

The MirrorWorld Anthology The Glass of Lead and Gold

The Glass of Lead and Gold Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness!

Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness! Reckless II

Reckless II Griffin's Feather

Griffin's Feather Emma and the Blue Genie

Emma and the Blue Genie Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom!

Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom! Inkheart ti-1

Inkheart ti-1 The Pirate Pig

The Pirate Pig Inkspell ti-2

Inkspell ti-2 The Petrified Flesh

The Petrified Flesh Inkdeath ti-3

Inkdeath ti-3 Ruffleclaw

Ruffleclaw Lilly and Fin

Lilly and Fin