- Home

- Cornelia Funke

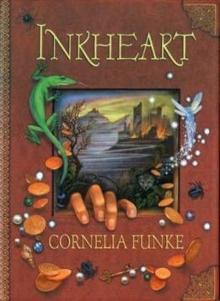

Inkheart Page 7

Inkheart Read online

Page 7

faintest idea how you set about comforting a girl of twelve, so she just told her, ‘Your mother always slept in this room,’ which was probably the worst thing she could have said. She quickly added, ‘Read a story if you can’t get to sleep,’ cleared her throat twice, and then went back through the dark, empty house to her own room.

Why did it suddenly strike her as so big and so empty? In all the years she had lived alone here it had never troubled her to know that only her books awaited her behind all the doors. It was a long time since she and her sisters had played hide-and-seek in the many rooms. How quietly they always had to slip past the library door …

Outside, the wind rattled the shutters of the windows. Heavens, I won’t be able to sleep a wink, thought Elinor. And then she thought of the book waiting beside her bed, and with a mixture of anticipation and a very guilty conscience she disappeared into her bedroom.

9

A Poor Exchange

A strong and bitter book-sickness floods one’s soul. How ignominious to be strapped to this ponderous mass of paper, print and dead man’s sentiment. Would it not be better, finer, braver to leave the rubbish where it lies and walk out into the world a free untrammelled illiterate Superman?

Solomon Eagle

Meggie didn’t sleep in her own bed that night. As soon as Elinor’s footsteps had died away she ran to Mo’s room. He hadn’t unpacked yet, and his bag stood open beside the bed. Only his books were on the bedside table, and a partly eaten chocolate bar. Mo loved chocolate. Even the mustiest old chocolate Santa Claus wasn’t safe from him. Meggie broke a square off the bar and put it in her mouth, but it tasted of nothing. Nothing but sadness.

Mo’s quilt was cold when she crept under it, and the pillow didn’t yet smell of him either, only of washing powder. Meggie put her hand under the pillow. Yes, there it was: not a book, a photograph. Meggie drew it out. It was a picture of her mother; Mo always kept it under his pillow. When she was little she believed that Mo had simply invented a mother for her one day because he thought she’d have liked to have one. He told wonderful stories about her. ‘Did I like her?’ Meggie always asked. ‘Yes, very much.’ – ‘Where is she?’ – ‘She had to go away when you were just three.’ – ‘Why?’ – ‘She just had to go away.’ – ‘A long way away?’ – ‘Yes, a very long way.’ – ‘Is she dead?’ – ‘No, I’m sure she isn’t.’ Meggie was used to the strange answers Mo gave to many of her questions. By the time she was ten she no longer believed in a mother made up by Mo, she believed in one who had simply gone away. These things happened. And as long as Mo was there she hadn’t particularly missed having a mother.

But now he was gone, and she was alone with Elinor and Elinor’s pebble eyes.

She took Mo’s sweater out of his bag and buried her face in it. It’s the book’s fault, she kept thinking. It’s all that book’s fault. Why didn’t he give it to Dustfinger? Sometimes, when you’re so sad you don’t know what to do, it helps to be angry. But then the tears came back again all the same, and Meggie fell asleep with the salty taste of them on her lips.

When she woke all of a sudden, her heart pounding and her hair damp with sweat, it all came back to her: the men, Mo’s voice, the empty road. I’ll go and look for him, thought Meggie. Yes, that’s what I’ll do. Outside the sky was just turning red. Not long now and the sun would rise. It would be better if she was gone before it got really light. Mo’s jacket was hanging over the chair under the window, as if he’d only just taken it off. Meggie took his wallet out of it – she’d need the money. Then she crept back to her room to pack a few things, only the essentials: a change of clothing and a photograph of herself and Mo, so that she could ask people if they’d seen him. Of course she couldn’t take her book-box. She thought of hiding it under the bed, but she decided to write Elinor a note instead:

Dear Elinor, she wrote, although she didn’t really think that was the correct way to address an aunt. I have to go and look for my father, she went on. Don’t worry about me. Well, Elinor wasn’t likely to do that anyway. And please don’t tell the police I’ve gone or they’ll be sure to bring me back. My favourite books are in my box. I’m afraid I can’t take them with me. Please look after them. I’ll come and fetch them as soon as I’ve found my father. Thank you. Meggie.

P.S.: I know exactly how many books there are in the box.

She crossed out that last sentence. It would only annoy Elinor, and who knew what she might do with the books then? Sell them, probably. After all, Mo had given them all particularly nice bindings. None of them was bound in leather, because Meggie didn’t like to think of a calf or a pig losing its skin for her books. Luckily, Mo understood how she felt. Many hundreds of years ago, he had once told Meggie, people made the bindings for particularly valuable books from the skin of unborn calves, charta virginea non nata, a pretty name for a terrible thing. ‘And those books,’ Mo had told her, ‘were full of the most wonderful words about love and kindness and mercy.’

While Meggie was packing her bag she did her best not to think, because if she did she knew she’d have to ask herself where she was going to search for Mo. She kept pushing the thought away, but all the same her hands slowed down, and at last she was standing beside her packed bag, no longer able to ignore the cruel little voice inside her. ‘Well then, where are you going to look, Meggie?’ it whispered. ‘Are you going to turn left or right when you reach the road? You don’t even know that. How far do you think you’ll get before the police pick you up? A twelve-year-old girl carrying a bag, with a wild story about a father who’s disappeared, and no mother they can take her back to.’

Meggie put her hands over her ears, but what use was that when the voice was inside her head? She stood like that for quite a long time. Then she shook her head until the voice stopped, and dragged her bag out into the corridor. It was heavy. Much too heavy. Meggie opened it again and put almost everything back in her room. She kept only a sweater, a book (she had to have at least one), the photo and Mo’s wallet. Now she could carry the bag as far as she had to.

She slipped quietly downstairs with the bag in one hand and the note for Elinor in the other. The morning sunlight was already filtering through the cracks of the shutters, but it was as silent in the big house as if even the books on the shelves were sleeping. Only the sound of quiet snoring came through Elinor’s bedroom door. Meggie really meant to push the note under the door, but it wouldn’t fit. She hesitated for a moment and then pressed the door-handle down. It was light in Elinor’s bedroom, even though the shutters were closed. The bedside lamp was switched on, so obviously Elinor had gone to sleep while she was reading. She was lying on her back with her mouth slightly open, snoring at the plaster angel on the ceiling above her. And she was clutching a book to her chest. Meggie recognised it at once.

She was beside the bed in an instant. ‘Where did you get that?’ she shouted, tugging the book out of Elinor’s arms, which were heavy with sleep. ‘That’s my father’s!’

Elinor woke as suddenly as if Meggie had tipped cold water over her face.

‘You stole it!’ cried Meggie, beside herself with rage. ‘And you brought those men here, yes, that’s what happened. You and that Capricorn are in this together! You had my father taken away, and who knows what you did with poor Dustfinger? You wanted that book from the start! I saw the way you looked at it – like something alive! It’s probably worth a million – or two million or three million …’

Elinor was sitting up in bed, staring at the flowers on her nightdress and saying not a word. She didn’t move until Meggie was struggling to get her breath back.

‘Finished?’ she asked. ‘Or are you planning to stand there yelling your head off until you drop dead?’ Her voice sounded as brusque as usual, but it had another note in it too – a touch of guilt.

‘I’m going to tell the police!’ cried Meggie. ‘I’ll tell them you stole the book and they ought to ask you where my father is.’

‘I saved you �

� and this book!’

Elinor swung her legs out of bed, went over to the window and opened the shutters.

‘Oh yes? And what about Mo?’ Meggie’s voice was rising again. ‘What’s going to happen when they realise he gave them the wrong book? It’s all your fault if they hurt him. Dustfinger said Capricorn would kill him if he didn’t hand over the book. He’ll kill him!’

Elinor put her head out of the window and took a deep breath. Then she turned round again. ‘What nonsense!’ she said crossly. ‘You think far too much of what that matchstick-eater says. And you’ve obviously read too many bad adventure stories. Kill your father? Heavens above, he’s not a secret agent or anything dangerous like that! He restores old books! It’s not exactly a life-threatening profession! I just wanted to take a look at the book in peace. That’s the only reason I swapped it round. How could I guess those villains would come here in the middle of the night to take your father away along with their precious book? All he told me was that some crazy collector had been badgering him for that book for years. How was I to know this collector wouldn’t shrink from breaking and entering, not to mention kidnapping? Even I wouldn’t think up an idea like that. Well, maybe for just one or two books in the world I might.’

‘But that’s what Dustfinger said. He said Capricorn would kill him!’ Meggie was clutching the book tightly, as if that were the only way of preventing yet more misfortunes from creeping out of it. It was as if she suddenly remembered Dustfinger’s voice again. ‘And the little creature’s screeching and struggling,’ she whispered, ‘would be as sweet as honey to him.’

‘What? Who are you talking about now?’ Elinor perched on the edge of the bed and made Meggie sit down beside her. ‘You’d better tell me everything you know about this business. Begin at the beginning.’

Meggie opened the book and leafed through the pages until she found the big ‘N’ with the animal that looked so like Gwin sitting on it.

‘Meggie! I’m talking to you!’ Elinor shook her roughly by the shoulders. ‘Who were you talking about just now?’

‘Capricorn.’ Meggie just whispered the name. Danger seemed to cling to it – to every single letter of it.

‘Capricorn. Go on. I’ve heard you mention that name a couple of times before. But who, for goodness’ sake, is this Capricorn?’

Meggie closed the book, stroked the binding, and looked at it from all sides. ‘It doesn’t give the title on the cover,’ she murmured.

‘No, not on the cover or inside.’ Elinor rose and went to her wardrobe. ‘There are a good many books where you can’t find the title straight away. After all, it’s a relatively modern habit to put it on the cover. When books were still bound so that the spines curved inwards the title might be on the side, if anywhere, but in most cases you found it out only when you opened the book. It wasn’t until bookbinders learned to make rounded spines that the title moved to the front of the book.’

‘Yes, I know!’ said Meggie impatiently. ‘But this isn’t an old book. I know what old books look like.’

Elinor looked at her ironically. ‘Oh, I apologise! I was forgetting you’re a real little expert. But you’re right, yes, this book isn’t very old. It was published almost exactly thirty-eight years ago. Ridiculously young for a book!’ She disappeared behind her open wardrobe door. ‘But of course it has a title all the same. It’s called Inkheart. I suspect your father intentionally bound it so that no one could identify it just from looking at the cover. You don’t even find the title on the first page, and when you look carefully you see that he’s removed it – the title page.’

Elinor’s nightdress landed on the carpet, and Meggie saw a pair of tights being put on over her bare legs.

‘We have to go to the police again,’ said Meggie.

‘What for?’ Elinor threw a sweater over the wardrobe door. ‘What are you going to tell them? Didn’t you notice the way those two policemen looked at us last night?’ Elinor imitated them: ‘“Oh yes, what was that again, Signora Loredan? Someone broke into your house after you’d been kind enough to switch off the burglar alarm? And then this amazingly cunning burglar stole just one book, although there are books worth millions in your library, and they took this girl’s father away after he’d offered to go with them in any case? Yes, very interesting. And it seems that these men were working for a man called Capricorn. Doesn’t that mean goat or something?” Heavens above, child!’ Elinor emerged from behind the wardrobe door. She was wearing an unattractive check skirt and a caramel-coloured sweater that made her look as pale as dough. ‘Everyone living around this lake thinks I’m crazy, and if we go back to the police with this story, then the news that Elinor Loredan has finally flipped will be all over the place. Which just goes to show that a passion for books is extremely unhealthy.’

‘You dress like an old granny,’ said Meggie.

Elinor looked down at herself. ‘Thank you very much,’ she said, ‘but comments on my appearance are uncalled-for. Anyway, I could be your granny. With a little stretch of the imagination.’

‘Have you ever been married?’

‘No, why would I want to? And could you now kindly stop making personal remarks? Hasn’t your father ever taught you that it’s bad manners?’

Meggie did not reply. She wasn’t sure herself why she had asked the question. ‘This book is very valuable, isn’t it?’ she asked.

‘What, Inkheart?’ Elinor took it from Meggie’s hand, stroked the binding and then gave it back. ‘I think so. Although you won’t find a single copy in any of the catalogues or lists of valuable books. But I’m sure that many collectors would offer your father a very great deal of money if word got around that he has what may be the only copy. Actually, I found out quite a lot about it, and I believe it’s not just a rare book but a good one too. I can’t give an opinion on that. I scarcely managed a dozen pages last night. When the first fairy appeared I fell asleep. I never was particularly keen on stories full of fairies and dwarves and all that stuff.’

Elinor went round behind the wardrobe door again, obviously to look at herself in a mirror. Meggie’s comment on her clothes seemed to be bothering her after all. ‘Yes, I think it is very valuable,’ she repeated thoughtfully. ‘Although it’s almost forgotten now. Hardly anyone seems to remember what it’s about, hardly anyone seems to have read it. You can’t even find it in libraries. But now and then these strange stories about it do crop up: they say it’s been forgotten only because all the copies that still existed were stolen. I expect that’s nonsense. Although it’s not just plants and animals that die out, so do books. Quite often, I’m sorry to say. I’m sure you could fill a hundred houses like this one to the roof with all the books that have disappeared for ever.’ Elinor closed the wardrobe door again, and pinned up her hair with clumsy fingers. ‘As far as I know the author’s still alive, but obviously he’s never done anything about getting his book reprinted – which strikes me as odd. I mean, you write a story so that people will read it, don’t you? Well, perhaps he doesn’t like his own story any more, or perhaps it just sold so badly that no publisher was willing to bring it out again. How would I know?’

‘All the same, I don’t think they stole it just because it’s valuable,’ muttered Meggie.

‘You don’t?’ Elinor laughed out loud. ‘My word, you really are your father’s daughter! Mortimer could never imagine people doing something bad for money, because money has never meant much to him. Do you have any idea what a book can be worth?’

Meggie looked at her crossly. ‘Yes, I do. But I still don’t think that’s the reason.’

‘I do. And Sherlock Holmes would think so too. Have you ever read those books, by the way? Wonderful stuff. Specially on rainy days.’ Elinor slipped her shoes on. She had strangely small feet for such a sturdily built woman.

‘Perhaps there’s some kind of secret in it,’ murmured Meggie, thoughtfully caressing the close-printed pages.

‘You mean something like invisible messag

es written in lemon juice, or a map hidden in one of the pictures showing where to find treasure?’ Elinor sounded so sarcastic that Meggie felt like wringing her short neck.

‘Why not?’ Meggie closed the book again and put it firmly under her arm. ‘Why else would they take Mo too? The book would have been enough.’

Elinor shrugged her shoulders.

Of course she can’t admit she never thought of that, Meggie told herself scornfully. She always has to be right!

Elinor looked at Meggie as if she had guessed her thoughts. ‘Listen, I tell you what, why don’t you read it?’ she said. ‘You really might find something that you don’t think belongs in the story. A few extra words here, a couple of unnecessary letters there – and there’s your secret message. The signpost pointing to the treasure. Who knows how long it will be before your father comes back? You’ll have to do something to pass the time here.’

Before Meggie could answer that one, Elinor bent to pick up a piece of paper lying on the carpet beside her bed. It was Meggie’s goodbye note. She must have dropped it when she saw the book in Elinor’s arms.

‘What on earth’s this?’ asked Elinor, when she had read it, frowning. ‘You were planning to go and look for your father? Where, for heaven’s sake? You’re even more foolish than I thought.’

Meggie pressed Inkheart close to her. ‘Who else is going to look for him?’ she said. Her lips began to tremble, and there wasn’t a thing she could do about it.

‘Well then, we’ll just have to go and look for him together!’ replied Elinor, sounding annoyed. ‘But first let’s give him a chance to come back. Do you think he’ll be pleased to get back here only to find you’ve disappeared, gone looking for him in the big wide world?’

Meggie shook her head. Elinor’s carpet was swimming before her eyes. A tear ran down her nose.

‘Right, that’s all settled, then,’ growled Elinor, offering Meggie a cotton handkerchief. ‘Blow your nose and then we’ll have breakfast.’

She wouldn’t let Meggie out of the house before she had eaten a roll and swallowed a glass of milk.

‘Breakfast is the most important meal of the day,’ she announced, buttering her own third slice of bread. ‘And what’s more, when your father gets back I don’t want you telling him I’ve been starving you. Like the wicked stepmother in the fairy tale, you know.’

An answer sprang to the tip of Meggie’s tongue, but she swallowed it along with the last of her roll, and took the book outside.

10

The Lion’s Den

Look. (Grown-ups skip this paragraph.) I’m not about to tell you this book has a tragic ending, I already said in the very first line how it was my favourite in all the world. But there’s a lot of bad stuff coming.

William Goldman,

The Princess Bride

Meggie sat on the bench behind the house. Dustfinger’s burnt-out torches were still stuck in the ground beside it. She didn’t usually hesitate so long before opening a book, but she was afraid of what was waiting for her inside this one. That was a brand-new feeling. She had never before been afraid of what a book would tell her. Far from it. Usually, she was so eager to let it lead her into an undiscovered world, one she had never been to before, that she often started to read at the most unsuitable moments. Both she and Mo often read at breakfast and, as a result, he had more than once taken her to school late. And she used to read under the desk at school too, and late at night in bed until Mo pulled back the covers and threatened to take all the books out of her room so that she’d get enough sleep for once. Of course he would never have done such a thing, and he knew she knew he wouldn’t, but for a few days after such a threat she would put her book under her pillow around nine in the evening and let it go on whispering to her in her dreams, so

Inkdeath

Inkdeath Inkheart

Inkheart Ghost Knight

Ghost Knight Inkspell

Inkspell The Golden Yarn

The Golden Yarn Fearless

Fearless The Thief Lord

The Thief Lord The Griffin's Feather

The Griffin's Feather Igraine the Brave

Igraine the Brave Reckless

Reckless When Santa Fell to Earth

When Santa Fell to Earth Dragon Rider

Dragon Rider Living Shadows

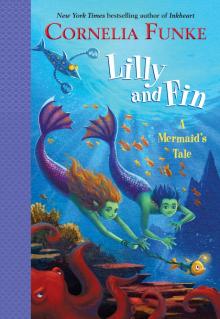

Living Shadows Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale

Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale The MirrorWorld Anthology

The MirrorWorld Anthology The Glass of Lead and Gold

The Glass of Lead and Gold Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness!

Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness! Reckless II

Reckless II Griffin's Feather

Griffin's Feather Emma and the Blue Genie

Emma and the Blue Genie Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom!

Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom! Inkheart ti-1

Inkheart ti-1 The Pirate Pig

The Pirate Pig Inkspell ti-2

Inkspell ti-2 The Petrified Flesh

The Petrified Flesh Inkdeath ti-3

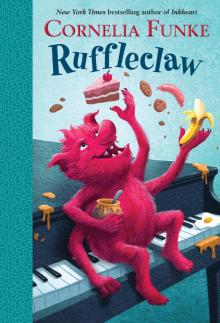

Inkdeath ti-3 Ruffleclaw

Ruffleclaw Lilly and Fin

Lilly and Fin