- Home

- Cornelia Funke

Inkspell Page 20

Inkspell Read online

Page 20

She didn’t know whether to laugh or weep first. She leaned over him and covered his face with kisses. And then she both laughed and wept.

26

Fenoglio’s Plan

All I need is a sheet of paper

and something to write with, and then

I can turn the world upside down.

Friedrich Nietzsche,

Die weisse und die schwarze Kunst

Two days had passed since the festivities at the castle: two days which Fenoglio had spent showing Meggie every nook and cranny of Ombra. ‘But today,’ he said, before they set off again after eating breakfast with Minerva, ‘today I’ll show you the river. It’s a steep climb down, not very easy for my old bones, but there’s nowhere better to talk in peace. And what’s more, if we’re in luck you may see some river-nymphs down there.’ Meggie would have loved to see a river-nymph. She had only come upon a water-nymph so far, in a rather muddy pond in the Wayless Wood, and as soon as Meggie’s reflection had fallen on the water the nymph had darted away. But what exactly did Fenoglio want to talk about in peace? It wasn’t hard to guess.

What was he going to ask her to read here this time? Or, rather, who was he going to ask her to read here – and where from? From another story written by Fenoglio himself?

The path down which he led her wound its way along steeply sloping fields where farmers were working, bent double in the morning sun. How hard it must be growing enough to eat to allow you to survive the winter. And then there were all the creatures who secretly attacked your few provisions: mice, mealworms, maggots, woodlice. Life was much more difficult in Fenoglio’s world, yet it seemed to Meggie that with every new day his story was spinning a magic spell around her heart, sticky as spiders’ webs, and enchantingly beautiful too …

Everything around her seemed so real by now. Her homesickness had almost disappeared.

‘Come on!’ Fenoglio’s voice startled her out of her thoughts. The river lay before them, shining in the sun, with faded flowers drifting on the water by its banks. Fenoglio took her hand and led her down the bank, to a place where large rocks stood. Meggie hopefully leaned over the slowly flowing water, but there were no river-nymphs in sight.

‘Well, they’re timid. Too many people about!’ Fenoglio looked disapprovingly at the women doing their washing nearby. He waved to Meggie to walk on until the voices died away, and only the rippling of the water could be heard. Behind them the roofs and towers of Ombra rose against the pale blue sky. The houses were crowded close inside the walls, like birds in a nest too small for them, and the black banners of the castle fluttered above them as if to inscribe the Laughing Prince’s grief on the sky itself.

Meggie clambered up on to a flat rock over the water’s edge. The river was not broad, but seemed to be deep, and its water was darker than the shadows on the opposite bank.

‘Can you see one?’ Fenoglio almost slipped off the wet rock as he joined her. Meggie shook her head. ‘What’s the matter?’ Fenoglio knew her well after the days and nights they had spent together in Capricorn’s house. ‘Not homesick again, are you?’

‘No, no.’ Meggie knelt down and ran her fingers through the cold water. ‘I just had that dream again.’

The previous day, Fenoglio had shown her Bakers’ Alley, the houses where the rich spice and cloth dealers lived, and every gargoyle, every carved flower, every richly adorned frieze with which the skilful stonemasons of Ombra had ornamented the buildings of the city. Judging by the pride Fenoglio displayed as he led Meggie past every corner of Ombra, however remote, he seemed to consider it all his own work. ‘Well, perhaps not every corner,’ he admitted, as she once tried getting him to go down an alley she hadn’t seen yet. ‘Of course Ombra has its ugly sides too, but there’s no need for you to bother your pretty head about them.’

It had been dark by the time they were back in his room under Minerva’s roof, and Fenoglio quarrelled with Rosenquartz because the glass man had spattered the fairies with ink. Even though their voices rose louder and louder, Meggie nodded off on the straw mattress that Minerva had sent up the steep staircase for her and that now lay under the window – and suddenly there was all that red, a dull red, shining, wet red, and her heart had started beating faster and faster, ever faster, until its violent thudding woke her with a start …

‘There, look!’ Fenoglio took her arm.

Rainbow scales shimmered under the watery surface of the river. At first Meggie almost took them for leaves, but then she saw the eyes looking at her, like human eyes yet very different, for they had no whites. The nymph’s arms looked delicate and fragile, almost transparent. Another glance, and then the scaly tail flicked in the water, and there was nothing left to be seen but a shoal of fish gliding by, silvery as a snail track, and a swarm of fire-elves like the elves she and Farid had seen in the forest. Farid. He had made a fiery flower blossom at her feet, a flower just for her. Dustfinger had certainly taught him many wonderful things.

‘I think it’s always the same dream, but I can’t remember. I just remember the fear – as if something terrible had happened!’ She turned to Fenoglio. ‘Do you think it really has?’

‘Nonsense!’ Fenoglio brushed the thought aside like a troublesome insect. ‘We must blame Rosenquartz for your bad dream. I expect the fairies sat on your forehead in the night because he annoyed them! They’re vengeful little things, and I’m afraid it makes no difference to them who they avenge themselves on.’

‘I see.’ Meggie dipped her fingers in the water again. It was so cold that she shivered. She heard the washerwomen laugh, and a fire-elf settled on her wrist. Insect eyes stared at her out of a human face. Meggie quickly shooed the tiny creature away.

‘Very sensible,’ Fenoglio said. ‘You want to be careful of fire-elves. They’ll burn your skin.’

‘I know. Resa told me about them.’ Meggie watched the elf go. There was a sore, red mark on her arm where it had settled.

‘My own invention,’ explained Fenoglio proudly. ‘They produce honey that lets you talk to fire. Very much sought after by fire-eaters, but the elves attack anyone who comes too close to their nests, and few know how to set about stealing the honey without getting badly burned. In fact, now that I come to think of it, probably no one but Dustfinger knows.’

Meggie just nodded. She had hardly been listening. ‘What did you want to talk to me about? You want me to read something, don’t you?’

A few faded red flowers drifted past on the water, red as dried blood, and Meggie’s heart began beating so hard again that she put her hand to her breast. What was the matter with her?

Fenoglio undid the bag at his belt and tipped a domed red stone out into his hand. ‘Isn’t it magnificent?’ he asked. ‘I went to get it this morning while you were still asleep. It’s a beryl, a reading stone. You can use it like spectacles.’

‘I know. What about it?’ Meggie stroked the smooth stone with her fingertips. Mo had several like it, lying on the window-sill of his workshop.

‘What about it? Don’t be so impatient! Violante is almost as blind as a bat, and her delightful son has hidden her old reading stone. So I bought her another, even though it was a ruinous price. I hope she’ll be so grateful that in return she’ll tell us a few things about her late husband! Yes, yes, I know I made up Cosimo myself, but it was long ago that I wrote about him. To be honest, I don’t remember that part particularly well, and what’s more … who knows how he may have changed, once this story took it into its head to go on telling itself?’

A horrible foreboding came into Meggie’s mind. No, he couldn’t be planning to do that. Not even Fenoglio would think up such an idea. Or would he?

‘Listen, Meggie!’ He lowered his voice, as if the women doing their washing upstream could hear him. ‘The two of us are going to bring Cosimo back!’

Meggie sat up straight, so abruptly that she almost slipped and fell into the river. ‘You’re crazy. Totally crazy! Cosimo’s dead!’

; ‘Can anyone prove it?’ She didn’t like Fenoglio’s smile one little bit. ‘I told you – his body was burned beyond recognition. Even his father wasn’t sure it was really Cosimo! He waited six months before he would have the dead man buried in the coffin intended for his son.’

‘But it was Cosimo, wasn’t it?’

‘Who’s going to say so? It was a terrible massacre. They say the fire-raisers had been storing some kind of alchemical powder in their fortress, and Firefox set it alight to help him get away. The flames enveloped Cosimo and most of his men, and later no one could identify the dead bodies found among the ruins.’

Meggie shuddered. Fenoglio, on the other hand, seemed greatly pleased by this idea. She couldn’t believe how satisfied he looked.

‘But it was him, you know it was!’ Meggie’s voice sank to a whisper. ‘Fenoglio, we can’t bring back the dead!’

‘I know, I know, probably not.’ There was deep regret in his voice. ‘Although didn’t some of the dead come back when you summoned the Shadow?’

‘No! They all fell to dust and ashes again only a few days later. Elinor cried her eyes out – she went to Capricorn’s village, even though Mo tried to persuade her not to, and there wasn’t anyone there either. They’d all gone. For ever.’

‘Hm.’ Fenoglio stared at his hands. They looked like the hands of a farmer or a craftsman, not hands that wielded only a pen. ‘So we can’t. Very well!’ he murmured. ‘Perhaps it’s all for the best. How would a story ever work if anyone could just come back from the dead at any time? It would lead to hopeless confusion; it would wreck the suspense! No, you’re right: the dead stay dead. So we won’t bring Cosimo back, just – well, someone who looks like him!’

‘Looks like him? You are crazy!’ whispered Meggie. ‘You’re a total lunatic!’

But her opinion did not impress Fenoglio in the slightest. ‘So what? All writers are lunatics! I promise you, I’ll choose my words very carefully, so carefully that our brand-new Cosimo will be firmly convinced he is the old one. Do you see, Meggie? Even if he’s only a double, he mustn’t know it. On no account is he to know it! What do you think?’

Meggie just shook her head. She hadn’t come here to change this world. She’d only wanted to see it!

‘Meggie!’ Fenoglio placed his hand on her shoulder. ‘You saw the Laughing Prince! He could die any day, and then what? It’s not just strolling players that the Adderhead strings up! He has his peasants’ eyes put out if they catch a rabbit in the forest. He forces children to work in his silver mines until they’re blind and crippled, and he’s made Firefox, who is a murderer and arsonist, his own herald!’

‘Oh yes? And who made him that way? You did!’ Meggie angrily pushed his hand away. ‘You always did like your villains best.’

‘Well, yes, maybe.’ Fenoglio shrugged, as if he were powerless to do anything about it. ‘But what was I to do? Who wants to read a story about two benevolent princes ruling a merry band of happy, contented subjects? What kind of a story would that be?’

Meggie leaned over the water and fished out one of the red flowers. ‘You like making them up!’ she said quietly. ‘All these monsters.’

Even Fenoglio had no reply to that. So they sat in silence while the women upstream spread their washing on the rocks to dry. It was still warm in the sun, in spite of the faded flowers that the river kept bringing in to the bank.

Fenoglio broke the silence at last. ‘Please, Meggie!’ he said. ‘Just this once. If you help me to get back in control of this story I’ll write you the most wonderful words to take you home again – whenever you like! Or if you change your mind because you like my world better, then I’ll bring your father here for you, and your mother … and even that bookworm woman, though from all you tell me she sounds a frightful person!’

That made Meggie laugh. Yes, Elinor would like it here, she thought, and she was sure Resa would like to see the place again. But not Mo. No, never.

She suddenly stood up and smoothed down her dress. Looking up at the castle, she imagined what it would be like if the Adderhead with his salamander gaze ruled up there. She hadn’t even liked the Laughing Prince much.

‘Meggie, believe me,’ said Fenoglio, ‘you’d be doing something truly good. You’d be giving a son back to his father, a husband back to his wife, a father back to his child – yes, I know he’s not a particularly nice child, but all the same! And you’d be helping to thwart the Adderhead’s plans. Surely that’s an honourable thing to do? Please, Meggie!’ He looked at her almost imploringly. ‘Help me. It’s my story, after all! Believe me, I know what’s best for it! Lend me your voice just once more!’

Lend me your voice … Meggie was still looking up at the castle, but she no longer saw the towers and the black banners. She was seeing the Shadow, and Capricorn lying dead in the dust.

‘All right, I’ll think about it,’ she said. ‘But now Farid is waiting for me.’

Fenoglio looked at her with as much surprise as if she had suddenly sprouted wings. ‘Oh, is he indeed?’ There was no mistaking the disapproval in his voice. ‘But I was going to go up to the castle with you to take Her Ugliness the beryl. I wanted you to hear what she has to say about Cosimo …’

‘I promised him!’ They had agreed to meet outside the city gates so that Farid wouldn’t have to pass the guards.

‘You promised? Well, never mind. You wouldn’t be the first girl to keep a suitor waiting.’

‘He is not my suitor!’

‘Glad to hear it! Since your father isn’t here, it’s up to me to keep an eye on you, after all.’ Fenoglio looked at her gloomily. ‘You really have grown! The girls here marry at your age. Oh, don’t look at me like that! Minerva’s second daughter has been married for five months, and she was just fourteen. How old is that boy? Fifteen? Sixteen?’

Meggie did not reply, but simply turned her back on him.

27

Violante

There is no frigate like a book

To take us lands away,

Nor any courser like a page

Of prancing poetry.

This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll;

How frugal is the chariot

That bears a human soul!

Emily Dickinson,

The Poems of Emily Dickinson

Fenoglio simply persuaded Farid to go up to the castle with them. ‘This will work out very well,’ he whispered to Meggie. ‘He can entertain the Prince’s spoilt brat of a grandson and give us a chance to get Violante to talk in peace.’

The Outer Courtyard lay as if deserted that morning. Only a few dry twigs and squashed cakes showed that there had been festivities here. Grooms, blacksmiths, stable lads were all going about their work again, but an oppressive silence seemed to weigh down on everyone within the walls. On recognizing Fenoglio, the guards of the Inner Castle let them pass without a word, and a group of men in grey robes, grave-faced, came towards them beneath the trees of the Inner Courtyard. ‘Physicians!’ muttered Fenoglio, uneasily watching them go. ‘More than enough of them to cure a dozen men to death. This bodes no good.’

The servant whom Fenoglio buttonholed outside the throne-room looked pale and tired. The Prince of Sighs, he told Fenoglio in a whisper, had taken to his bed during his grandson’s celebrations and hadn’t left it since. He would not eat or drink, and he had sent a messenger to the stonemason carving his sarcophagus telling him to hurry up about it.

But they were allowed in to visit Violante. The Prince would see neither his daughter-in-law nor his grandson. He had sent even the physicians away. He would have no one near him but his furry-faced page Tullio.

‘She’s where she ought not to be, again!’ The servant was whispering as if he could be heard by the sick Prince in his apartments as he led them through the castle. A carved likeness of Cosimo looked down on them in every corridor. Now that Meggie knew about Fenoglio’s plans, the stony eyes made her even more uncomfortable. ‘

They all have the same face!’ Farid whispered to her, but before Meggie could explain why the servant was beckoning them silently up a spiral staircase.

‘Does Balbulus still ask such a high price for letting Violante into the library?’ asked Fenoglio quietly as their guide stopped at a door, which was adorned with brass letters.

‘Poor thing, she’s given him almost all her jewellery,’ the servant whispered back. ‘But there you are, he used to live in the Castle of Night, didn’t he? Everyone knows that those who live on the other side of the forest are greedy folk. With the exception of my mistress.’

‘Come in!’ called a bad-tempered voice when the servant knocked. The room they entered was so bright that it made Meggie blink after walking through all those dark passages and up the dark stairs. Daylight fell through high windows on to several intricately carved desks. The man standing at the largest of them was neither young nor old, and he had black hair and brown eyes which looked at them without any cordiality as he turned to them.

‘Ah, the Inkweaver!’ he said, reluctantly putting down the hare’s foot he held in his hand. Meggie knew what it was for; Mo had told her often enough. Rubbing parchment with a hare’s foot made it smooth. And there were the colours whose names Mo had repeated over and over to her. Tell me again! How often she had plagued Mo with that demand! She never tired of the sound of them: lapis lazuli, orpiment, violet, malachite green. What makes them still shine like that, Mo? she had asked. After all, they’re so old! What are they made of? And Mo had told her – told her how you made them, all those wonderful colours that shone even after hundreds of years as if they had been stolen from the rainbow, now protected from air and light between the pages of books. To make malachite green you pounded wild iris flowers and mixed them with yellow lead oxide; the red was made from murex shells and cochineal insects … they had so often stood together looking at the pictures in one of the valuable manuscripts that Mo was to free from the grime of many years. Look at those delicate tendrils, he had said, can you imagine how fine the pens and brushes must be to paint something like that, Meggie? He was always complaining that no one could make such implements any more. And now she saw them with her own eyes, pens as fine as hairs and tiny brushes, whole sets of them standing in a glazed jug: brushes that could

Inkdeath

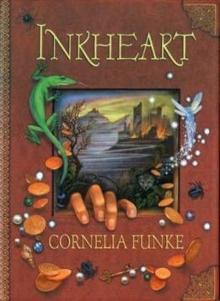

Inkdeath Inkheart

Inkheart Ghost Knight

Ghost Knight Inkspell

Inkspell The Golden Yarn

The Golden Yarn Fearless

Fearless The Thief Lord

The Thief Lord The Griffin's Feather

The Griffin's Feather Igraine the Brave

Igraine the Brave Reckless

Reckless When Santa Fell to Earth

When Santa Fell to Earth Dragon Rider

Dragon Rider Living Shadows

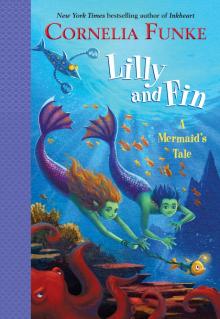

Living Shadows Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale

Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale The MirrorWorld Anthology

The MirrorWorld Anthology The Glass of Lead and Gold

The Glass of Lead and Gold Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness!

Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness! Reckless II

Reckless II Griffin's Feather

Griffin's Feather Emma and the Blue Genie

Emma and the Blue Genie Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom!

Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom! Inkheart ti-1

Inkheart ti-1 The Pirate Pig

The Pirate Pig Inkspell ti-2

Inkspell ti-2 The Petrified Flesh

The Petrified Flesh Inkdeath ti-3

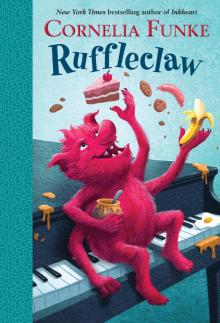

Inkdeath ti-3 Ruffleclaw

Ruffleclaw Lilly and Fin

Lilly and Fin