- Home

- Cornelia Funke

Inkdeath Page 19

Inkdeath Read online

Page 19

To Blame

Time, let me vanish. Then what we separate by our very own presence can come together.

Audrey Niffenegger,

The Time Traveller’s Wife

Resa waited among the graves until day began to dawn, but Mo did not come back.

She felt Roxane’s pain now, except that she didn’t even have a dead man to mourn. Mo was gone as if he had never existed. The story had swallowed him up, and she was to blame.

Meggie was crying. The Strong Man held her in his arms while tears ran down his own broad face.

‘It’s your fault!’ Meggie had kept shouting, pushing Resa and Farid away, not even letting the Prince comfort her. ‘You two persuaded him! Why did I save him after Mortola shot him, if they were going to take him now?’

‘I’m so sorry. I really am so very sorry.’

Orpheus’s voice still clung to Resa’s skin like something venomously sweet. When the White Women disappeared, he had stood there as if waiting for something, making an effort to hide the smile that kept returning to his lips. But Resa had seen it. Indeed she had … and so had Farid.

‘What have you done?’ He had seized Orpheus by his fine clothes and hammered at the man’s chest with his fists. Orpheus’s bodyguard tried to grab Farid, but the Strong Man held him off.

‘You filthy liar!’ Farid had cried, sobbing. ‘You double-tongued snake! Why didn’t you ask them anything? You were never going to ask them anything, were you? You just wanted them to take Silvertongue! Ask him! Ask him what else he wrote! He didn’t just write the words he promised Silvertongue – there was a second sheet too! He thinks I don’t know what he gets up to because I can’t read – but I can count. There were two sheets – and his glass man says he was reading out loud last night.’

He’s right, a voice whispered inside Resa. Oh God, Farid is right!

Orpheus, however, had taken great pains to look genuinely indignant. ‘What’s all this stupid talk?’ he had cried. ‘Do you think I’m not disappointed myself? How can I help it if they took him away with them? I’ve fulfilled my part of the bargain! I wrote exactly what Mortimer asked for! But did I get a chance to ask them about Dustfinger? No! All the same, I won’t ask for my words back. I hope it’s clear to all of you here,’ and he looked at the Black Prince, who still had his sword in his hand, ‘that I’m the one who gets nothing out of this deal!’

The words he had written were still tucked into Resa’s belt. She had been going to throw them after him when he rode away, but then she had kept them after all. The words that were to take them back … she hadn’t even looked to see what they said. They had been bought at too high a price. Mo was gone, and Meggie would never forgive her. She had lost them both, again, for the sake of those words.

Resa leant her forehead against the gravestone beside her. It was a child’s grave; a tiny shirt lay on it. I’m so sorry. Once again she remembered Orpheus’s deep, soft voice mingled with her daughter’s sobbing. Farid was right. Orpheus was a liar. He had written what was to happen, and his voice made it come true. He had got rid of Mo because he was jealous of him, as Meggie had always said – and she had helped him to do it.

With trembling fingers she unfolded the paper that Mo had tucked into her belt. It was damp with dew, and Orpheus’s coat of arms stood above the words, lavish as a prince’s. Farid had told them how he had commissioned it from a designer of crests in Ombra – a crown for the lie that he came from a royal family, a pair of palm trees for the foreign land he claimed to come from, and a unicorn, its winding horn black with ink.

Mo’s own bookbinder’s mark was a unicorn too. Resa felt tears coming again. The words blurred before her eyes as she began to read them. The description of Elinor’s house was a little stilted. But Orpheus had found the right words for her homesickness and her fear that this story could make her husband into someone else … how did he know so well what went on in her heart? From you yourself, Resa, she thought bitterly. You took all your despair to him. She read on – and stopped short.

And mother and daughter went away, back to the house full of books, but the Bluejay stayed – promising to follow them when the time came and he had played his part …

I wrote exactly what Mortimer asked for! she heard Orpheus saying, his voice full of injured innocence.

No. It couldn’t be true! Mo had wanted to go with her and Meggie … hadn’t he?

You’ll never know the answer, she told herself, bent double over the little grave from the pain in her heart. She thought she heard the child inside her weeping too.

‘Let’s go, Resa!’ The Black Prince was there beside her, offering her his hand. His face showed no reproach, although it was sad, very sad. Nor did he ask about the words that Orpheus had written. Perhaps he believed the Bluejay had really been an enchanter after all. The Black Prince and the Bluejay, the two hands of justice – one black, the other white. Now there was only the Prince again.

Resa took his hand and rose to her feet with difficulty. Go? Go where? she felt like asking. Back to the camp, where an empty tent is waiting and your men will look at me with more hostility than ever?

Doria brought her horse. The Strong Man was still standing with Meggie, his big face as tearstained as her daughter’s. He avoided her eyes. So he too blamed her for what had happened.

Go where? Back?

Resa was still holding the sheet of paper with Orpheus’s words on it. Elinor’s house. How would it feel to go back there without Mo? If Meggie would agree to read the words at all. Elinor, I’ve lost Mo. I wanted to protect him, but … no, she didn’t want to have to tell that story. There was no going back. There was nothing any more.

‘Come along, Meggie.’ The Black Prince beckoned Meggie over. He was about to put her up with Resa on her horse, but Meggie recoiled.

‘No. I’ll ride with Doria,’ she said.

Doria brought his horse to her side. Farid gave the other boy a scowl when he lifted Meggie up behind him.

‘And why are you still here?’ Meggie snapped at him. ‘Still hoping to see Dustfinger suddenly materialize in front of you? He won’t come back, any more than my father will – but I’m sure Orpheus will take you in again, after all you’ve done for him!’

Farid flinched like a beaten dog at every word. Then he turned in silence and went to his donkey. He called for the marten, but Jink didn’t come, and Farid rode away without him.

Meggie didn’t watch him go.

She turned to Resa. ‘You needn’t think I’m going back with you!’ she said sharply. ‘If you need a reader for your precious words, go to Orpheus, like you did before!’

Again, the Black Prince didn’t ask what Meggie was talking about, although Resa saw the question on his weary face. He stayed at Resa’s side as they rode the long way back. The sun claimed hill after hill for its own, but Resa knew that night would not end for her. It would live in her heart from now on. The same night, for ever and ever. Black and white at the same time, like the women who had taken Mo away with them.

25

The End and the Beginning

HERE IS A SMALL FACT. You are going to die.

Markus Zusak,

The Book Thief

They brought it all back: the memory of pain and fear, of the burning fever and their cold hands on his heart. But this time everything was different. The White Women touched Mo and he did not fear them. They whispered the name that they thought was his, and it sounded like a welcome. Yes, they were welcoming him in their soft voices, heavy with longing, the voices he heard so often in his dreams – as if he were a friend who had been away for a long time, but had come back to them at last.

There were many of them, so many. Their pale faces surrounded him like mist, and everything else disappeared beyond it: Orpheus, Resa, Meggie, the Black Prince, who had been standing beside him only a moment ago. Even the stars vanished, and so did the ground beneath his feet. Suddenly he was standing on rotting leaves. Their fragrance hung sweet and

heavy in the cold air. Bones lay among the leaves, pale and polished. Skulls. Arm bones and leg bones. Where was he?

They’ve taken you away with them, Mortimer, he thought. Just as they took Dustfinger.

Why didn’t the idea make him afraid?

He heard birds above him, many birds, and when the White Women withdrew he saw air-roots overhead, hanging from a dark height like cobwebs. He was inside a tree as hollow as an organ pipe and as tall as the castle towers of Ombra. Fungi grew from its wooden sides, casting a pale green light on the nests of birds and fairies. Mo put out his hand to the roots to see if his fingers still had any feeling in them. Yes, they did. He ran them over his face, felt his own skin, the same as ever, warm. What did that mean? Wasn’t this death, after all?

If not, what was it? A dream?

He turned, still as if he were asleep, and saw beds of moss. Moss-women slept on them, their wrinkled faces as ageless in death as in life. But on the last mossy bed lay a familiar figure, his face as still as when Mo had last seen it. Dustfinger.

Roxane had kept the promise she made in the old mine. And he will look as if he were only sleeping long after my hair is white, for I know from Nettle how you go about preserving the body even when the soul is long gone.

Hesitantly, Mo approached the motionless figure. Without a word, the White Women made way for him.

Where are you, Mortimer, he wondered? Is this still the world of the living, even though the dead sleep here?

Dustfinger did indeed look as if he were sleeping. A peaceful, dreamless sleep. Was this where Roxane visited him? Presumably it was. But how did he himself come to be here?

‘Because this is the friend you wanted to ask about, isn’t he?’ The voice came from above, and when Mo looked up into the darkness he saw a bird sitting among the web of roots, a bird with gold plumage and a red mark on its breast. It was staring down at him from a bird’s round eyes, but the voice that came from its beak was the voice of a woman.

‘Your friend is a welcome guest here. He has brought us fire, the only element that does not obey me. And my daughters would gladly bring you here too, because they love your voice, but they know that voice needs the breath of living flesh. And when I ordered them to bring you here all the same, as your penalty for binding the White Book, they persuaded me to spare you, telling me you have a plan which will appease me.’

‘And what might that be?’ It was strange to hear his own voice in this place.

‘Don’t you know? Even though you’re ready to part with everything you love for it? You are going to bring me the man you took from me. Bring me the Adderhead, Bluejay.’

‘Who are you?’ Mo looked at the White Women. Then he looked at Dustfinger’s still face.

‘Guess.’ The bird ruffled up its golden feathers, and Mo saw that the mark on its breast was blood.

‘You are Death.’ Mo felt the word heavy on his tongue. Could any word be heavier?

‘Yes, so they call me, although I might be called by so many other names!’ The bird shook itself, and golden feathers covered the leaves at Mo’s feet. They fell on his hair and shoulders, and when he looked up again there was only the skeleton of a bird sitting among the roots. ‘I am the end and the beginning.’ Fur sprouted from the bones. Pointed ears grew on the bare skull. A squirrel was looking down at Mo, clutching the roots with tiny paws, and the voice with which the bird had spoken now came from its little mouth.

‘The Great Shape-Changer, that’s the name I like!’ The squirrel shook itself in its own turn, lost its fur, tail and ears and became a butterfly, a caterpillar at his feet, a big cat with a coat as dappled as the light in the Wayless Wood – and finally a marten that jumped on to the bed of moss where Dustfinger lay, and curled up at the dead man’s feet.

‘I am the beginning of all stories, and their end,’ it said in the voice of the bird, in the voice of the squirrel. ‘I am transience and renewal. Without me nothing is born, because without me nothing dies. But you have interfered with my work, Bluejay, by binding the Book that ties my hands. I was very angry with you for that, terribly angry.’

The marten bared its teeth, and Mo felt the White Women coming close to him again. Was he about to die now? His chest felt tight, he was breathing with difficulty, as he had when he felt them near him before.

‘Yes, I was angry,’ whispered the marten, and its voice was the voice of a woman, but it suddenly sounded old. ‘However, my daughters calmed my rage. They love your heart as much as your voice. They say it is a great heart, very great, and it would be a pity to break it now.’

The marten fell silent, and suddenly the whispering that Mo had never forgotten came again. It surrounded him; it was everywhere. ‘Be on your guard! Be on your guard, Bluejay!’

Be on his guard against what? The pale faces were looking at him. They were beautiful, but they blurred as soon as he tried to see them more distinctly.

‘Orpheus!’ whispered the pale lips.

And suddenly Mo heard Orpheus’s voice. Its melodious sound filled the hollow tree like a cloyingly sweet fragrance. ‘Hear me, Master of the Cold,’ said the poet. ‘Hear me, Master of Silence. I offer you a bargain. I send you the Bluejay, who has made mock of you. He will believe that he has only to call on your pale daughters, but I am offering him to you as the price for the Fire-Dancer. Take him, and in return send Dustfinger back to the land of the living, for his tale is not yet told to its end. But the Bluejay’s story lacks only one chapter, and your White Women shall write it.’ So the poet wrote and so he read, and as always his words came true. The Bluejay, presumptuous as he was, summoned the White Women, and Death did not let him go again. But the Fire-Dancer came back, and his story had a new beginning.

Be on your guard …

It was a few moments before Mo really understood. Then he cursed his stupidity in trusting the man who had nearly killed him once already. He desperately tried to remember the words Orpheus had written for Resa. Suppose he was trying to make an end of Meggie and Resa as well? Remember, Mo! What else did he write?

‘Yes, you were indeed stupid,’ Death’s voice mocked him. ‘But he was even more stupid than you. He thinks I can be bound with words, I who rule the land where there are no words, although all words come from it. Nothing can bind me, only the White Book, because you have filled its pages with white silence. Almost daily, the man it protects sends me a poor wretch he has killed as a messenger of his mockery. I would happily melt the flesh from your bones for that! But my daughters read your heart like a book, and they assure me that you will not rest until the man whom the Book protects is mine again. Is that true, Bluejay?’

The marten lay down on Dustfinger’s unmoving breast.

‘Yes!’ whispered Mo.

‘Good. Then go back and rid the world of that Book. Fill it with words before spring comes, or winter will never end for you. And I will take not only your life for the Adderhead’s, but your daughter’s too, because she helped you to bind the Book. Do you understand, Bluejay?’

‘Why two?’ asked Mo hoarsely. ‘How can you ask for two lives in return for one? Take mine, that’s enough.’

But the marten only stared at him. ‘I fix the price,’ it said. ‘All you have to do is pay it.’

Meggie. No. No. Go back, Resa, Mo thought. Get Meggie to read what Orpheus wrote and go back! Anything is better than this. Go back! Quickly!

But the marten laughed. And once again it sounded like an old woman’s laughter.

‘All stories end with me, Bluejay,’ Death said. ‘You will find me everywhere.’ And as if to prove it, the marten turned into the one-eared cat that liked to steal into Elinor’s garden to hunt her birds. The cat jumped nimbly off Dustfinger’s breast and rubbed around Mo’s legs. ‘Well, what do you say, Bluejay? Do you accept my conditions?’

And I will take not only your life for the Adderhead’s but your daughter’s too.

Mo glanced at Dustfinger. His face looked so much more peaceful in death than it h

ad in life. Had he met his younger daughter on the other side, and Cosimo, and Roxane’s first husband? Were all the dead in the same place?

The cat sat down in front of him and stared at him.

‘I accept,’ said Mo, so hoarsely that he could hardly make out his own words. ‘But I make a condition too: give me the Fire-Dancer to go with me. My voice stole ten years of his life. Let me give them back to him. And there’s another thing … don’t the songs say that the Adderhead’s death will come out of the fire?’

The cat crouched down. Fur fell red on the rotting leaves. Bones covered themselves with flesh and feathers again, and the gold-mocker with its bloodstained breast fluttered up to settle on Mo’s shoulder.

‘You like to make what the songs say come true, do you?’ the bird whispered to him. ‘Very well, I will give him to you. Let the Fire-Dancer live again. But if spring comes and the Adderhead is still immortal, his heart will stop beating at the same time as yours – and your daughter’s.’

Mo felt dizzy. He wanted to seize the bird and wring its golden neck to silence that voice, so old and pitiless, with irony in every word. Meggie. He almost stumbled as he went to Dustfinger’s side once more.

This time the White Women were reluctant to make way for him.

‘As you see, my daughters don’t like to let him go,’ said the old woman’s voice. ‘Even though they know he will come back.’

Mo looked at the motionless body. The face was indeed so much more tranquil than it had been in life, and all of a sudden he wasn’t sure whether he was really doing Dustfinger a favour by calling him back.

The bird was still on his shoulder, so light in weight, so sharp of claw.

‘What are you waiting for?’ asked Death. ‘Call him!’

And Mo obeyed.

26

Inkdeath

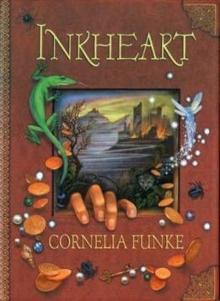

Inkdeath Inkheart

Inkheart Ghost Knight

Ghost Knight Inkspell

Inkspell The Golden Yarn

The Golden Yarn Fearless

Fearless The Thief Lord

The Thief Lord The Griffin's Feather

The Griffin's Feather Igraine the Brave

Igraine the Brave Reckless

Reckless When Santa Fell to Earth

When Santa Fell to Earth Dragon Rider

Dragon Rider Living Shadows

Living Shadows Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale

Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale The MirrorWorld Anthology

The MirrorWorld Anthology The Glass of Lead and Gold

The Glass of Lead and Gold Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness!

Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness! Reckless II

Reckless II Griffin's Feather

Griffin's Feather Emma and the Blue Genie

Emma and the Blue Genie Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom!

Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom! Inkheart ti-1

Inkheart ti-1 The Pirate Pig

The Pirate Pig Inkspell ti-2

Inkspell ti-2 The Petrified Flesh

The Petrified Flesh Inkdeath ti-3

Inkdeath ti-3 Ruffleclaw

Ruffleclaw Lilly and Fin

Lilly and Fin