- Home

- Cornelia Funke

Inkdeath Page 16

Inkdeath Read online

Page 16

‘Curse you!’ she said. ‘I wish I could call up the White Women myself and get them to take you away, here and now.’

She went down the steps outside the door unsteadily, as if her knees were trembling, but she did not turn back again.

‘Close the door, it’s cold!’ ordered Orpheus, and Brianna obeyed. But Orpheus himself remained standing there at the top of the stairs, staring at the closed door.

Farid looked uncertainly up at him. ‘Do you really believe Silvertongue can summon the White Women?’

‘Ah, so you were eavesdropping. Good.’

Good? What did that mean?

Orpheus stroked back his pale hair. ‘I’m sure you know where Mortimer is hiding at the moment, don’t you?’

‘Of course not! No one—’

‘Spare me the lies!’ snapped Orpheus. ‘Go to him. Tell him why his wife came to see me, and ask if he’s prepared to pay the price I demand for my words. And if you want to see Dustfinger again, the answer you bring me back had better be yes. Understand?’

‘The Fire-Dancer’s dead!’ Nothing in Brianna’s voice showed that she was speaking of her father.

Orpheus gave a little laugh. ‘Well, so was Farid, my beauty, but the White Women were ready to do a deal. Why wouldn’t they do the same thing again? It just has to be made attractive to them, and I think I now know how. It’s like fishing. You only need the right bait.’

What kind of bait did he mean? What was more desirable to the White Women than the Fire-Dancer? Farid didn’t want to know the answer. All he wanted was to think that all might yet end well. That bringing Orpheus here had been right after all …

‘What are you standing around for?’ Orpheus shouted down at him. ‘Get moving! And you,’ he added to Brianna, ‘bring me something to eat. I think it’s time for a new Bluejay song. And this time I, Orpheus, will write it!’

Farid heard him humming to himself as he returned to his study.

19

Soldiers’ Hands

Does the walker choose the path or the path the walker?

Garth Nix,

Sabriel

Ombra seemed more than ever like a city of the dead as Resa went back to the stable where she had left her horse. In the silence among the buildings she kept hearing Orpheus saying the same words over and over again, as clearly as if he were walking behind her: But I hope that when his head’s on a spike above the castle gates you’ll remember I could have kept him alive. Her tears almost blinded her as she stumbled through the night. What was she to do? Oh, what was she to do? Go back? No. Never.

She stopped.

Where was she? Ombra was a labyrinth of stone, and the years when she had known her way around its narrow streets were long gone.

Her own footsteps echoed in her ears as she walked on. She was still wearing the boots she had on when Orpheus read Mo and her here. He had almost killed Mo once already. Had she forgotten that?

A hiss overhead made her jump. It was followed by a dull crackling, and above the castle the night turned as scarlet as if the sky had caught fire. Sootbird was entertaining the Milksop and his guests by feeding the flames with alchemical poisons and menace until they writhed, instead of dancing as they used to dance for Dustfinger.

Dustfinger. Yes, she wanted him to come back too, and her heart froze when she imagined him lying among the dead. But it froze even more when she thought of the White Women reaching their hands out to Mo for a second time. Yet wouldn’t they come for him anyway, if he stayed in this world? Your husband will die in this story …

What was she to do?

The sky above her turned sulphurous green; Sootbird’s fire had many colours. The street down which she was walking, faster all the time, ended in a square she had never seen before. Dilapidated houses stood here. A dead cat lay in one doorway. At a loss, she went over to the well in the middle of the square – and spun around when she heard footsteps behind her. Three men moved out of the shadows among the buildings. Soldiers wearing the Adderhead’s colours.

Now what, she wondered? She had a knife with her, but what use was that against three swords? One of the men had a crossbow too. She had seen only too often what bolts from such a weapon could do. You should have worn men’s clothes, she told herself. Hasn’t Roxane told you often enough that no woman in Ombra goes out after dark, for fear of the Milksop’s men?

‘Well? I suppose your man’s as dead as all the rest, right?’

The soldier facing her was not much taller than she was, but the other two towered more than a head above her.

Resa looked up at the houses, but who was going to come to her aid? Fenoglio lived on the other side of Ombra, and Orpheus – well, even if he could hear her from here, would he and his gigantic servant help her after she’d refused to do a deal with him? Try it, Resa. Scream! Perhaps Farid at least will come and help you. But her voice failed her, as it had when she’d lost it in this world for the first time …

Only one window showed a light in the surrounding houses. An old woman put her head out, and hastily retreated when she saw the soldiers. Resa seemed to hear Mo saying, ‘Have you forgotten what this world is made of?’ So if it really consisted only of words, what would those words say about her? But there was a woman there who was lost twice in the Inkworld, and the second time she never found her way back again.

Two of the soldiers were now right behind her. One of them put his hands on her hips. Resa felt as if she had read about what was now happening already somewhere, sometime … stop trembling, she told herself. Hit him, claw at his eyes! Hadn’t Meggie told her how to defend herself if something like this ever happened?

The smallest of the three men came close to her, a dirty, expectant smile on his narrow lips. What did it feel like to get pleasure out of other people’s fear?

‘Leave me alone!’ At least her voice was obeying her again. But no doubt such voices were often heard in Ombra by night.

‘Why would we want to do that?’ The soldier behind her smelt of Sootbird’s fire. His hands reached out for her. The others laughed. Their laughter was almost the worst thing of all. Through the sound of it, however, Resa thought she heard something else. Footsteps – light, quick footsteps. Farid?

‘Take your hands off me!’ This time she shouted it as loud as she could, but it wasn’t her voice that made the men spin round.

‘Let her go. At once.’

Meggie’s voice sounded so grown-up that at first Resa didn’t realize it was her daughter’s. She walked out from among the houses holding herself very upright, just as she had walked into the arena that was the scene of Capricorn’s festivities.

The soldier holding Resa dropped his hands like a boy caught doing something wrong, but when he saw no one but a girl step out of the darkness he made a grab for his victim again.

‘Another one?’ The smaller man turned and sized Meggie up. ‘All the better. See that, you two? What did I tell you about Ombra? It’s a place full of women, so it is!’

Stupid words, and they were his last. The knife thrown by the Black Prince hit him in the back. Like shadows coming to life, the Prince and Mo emerged from the night. The soldier holding Resa pushed her away and drew his sword. He shouted a warning to the other man, but Mo killed them both so quickly that Resa felt she hadn’t even had time to draw breath. Her knees gave way, and she had to lean against the nearest wall. Meggie ran to her, asking anxiously if she was injured. But Mo just looked at her.

‘Well? Is Fenoglio writing again?’ That was all he said.

He knew why she had ridden here. Of course.

‘No!’ she whispered. ‘No, and he won’t write anything either. Nor will Orpheus.’

The way he was looking at her! As if he didn’t know whether he could believe what she said. He’d never looked at her like that before. Then he turned without a word, and helped the Prince to haul the dead men away into a side street.

‘We’re going back through the dyers’ stream!’ Meggie whispered

to her. ‘Mo and the Prince have killed the guards there.’

So many men dead, Resa. Just because you want to go home. There was blood all over the paving stones, and when Mo dragged away the soldier who had been holding her, the man’s eyes still seemed to stare at her. Was she sorry for him? No. But it sent a shiver down her spine to hear her daughter, too, speak so casually of killing. And what did Mo feel about it? Did he feel anything any more? She saw him wiping the blood off his sword with one of the dead men’s cloaks, and looking her way. Why couldn’t she read his thoughts in his eyes now, as she used to?

Because it was the Bluejay she saw there. And this time she had summoned him herself.

The walk to the dye works seemed endless. Sootbird’s fire was still lighting up the sky, and they twice had to hide from a troop of drunken soldiers, but finally the acrid smell of the dyers’ vats rose to their nostrils. Resa covered her mouth and nose with her sleeve when they came to the stream that carried the effluent away to the river through a grating in the city wall, and as she followed Mo into the stinking liquid she felt so sick that she could hardly take a deep enough breath to plunge down under the grating herself.

As the Black Prince helped her to the bank she saw one of the dead guards lying among the bushes. The blood on his chest looked like ink in the starless night, and Resa began crying. She couldn’t stop, not even when they finally reached the river and washed the stinking water out of their hair and clothes as best they could.

Two robbers were waiting with horses further along the bank, at the place where the river-nymphs swam and the women of Ombra dried their washing on the flat rocks by the waterside. Doria was there too, without his brother the Strong Man. He put his shabby cloak around Meggie’s shoulders when he saw how wet she was. Mo helped Resa into the saddle, but still said not a word. His silence made her shiver more than her wet clothes, and it was the Black Prince and not Mo who brought her a blanket. Had Mo told the Prince what she had gone to do in Ombra? No, surely not. How could he have explained without telling him what power words had in this world?

Meggie knew why she had ridden to Ombra too. Resa saw it in her eyes. They were watchful – as if her daughter were wondering uneasily what she would do next. Suppose Meggie learnt that she’d even asked Orpheus for help? Would she understand that the only reason had been Resa’s fears for her father?

It was beginning to rain as they set off. The wind drove the icy raindrops into their faces, and above the castle the sky glowed dark red, as if Sootbird were sending a warning after them. Doria fell behind on the Prince’s orders, to obliterate their tracks, and Mo rode ahead in silence. When he looked round once his glance was for Meggie, not her, and Resa was thankful for the rain on her face that kept anyone from seeing her tears.

20

A Sleepless Night

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Wendell Berry,

The Peace of Wild Things

‘I’m sorry.’ Resa meant it.

I’m sorry. Two words. She whispered them again and again, but Mo sensed what she was really thinking behind her words: she was a captive again. Capricorn’s fortress, his village in the mountains, the dungeons, the Castle of Night … so many prisons. Now a book was keeping her prisoner, the same book that had imprisoned her once before. And when she’d tried to escape, he had brought her back.

‘I’m sorry too,’ he said. He said it as often as she did – and knew that she was waiting to hear very different words. Very well, let’s go back, Resa. We’ll find a way somehow! But he didn’t say it, and the unspoken words gave rise to a silence they had never known, even when Resa was mute.

At last they lay down to sleep, although the sky was growing lighter outside, exhausted by the fear they had both felt and by what they didn’t say to each other. Resa fell asleep quickly, and as he looked at her sleeping face he remembered all the years when he had longed to see her asleep beside him. But even that idea brought him no peace – and at last he left Resa alone with her dreams.

He stepped out into the waning night, passed the guards, who ribbed him about the stench of the dye works that still clung to his clothes, and walked through the narrow ravine where they had set up camp, as though, if he only strained his ears hard enough, the Inkworld would whisper to him and tell him what to do.

He knew, only too well, what he wanted to do …

Finally he sat down by one of the ponds that had once been a giant’s footprint, and watched the dragonflies whirring above the cloudy water. In this world they really did look like tiny winged dragons, and Mo loved sitting there, following their strange shapes with his eyes and imagining how huge the giant who had left such a footprint must have been. Only a few days ago he and Meggie had waded into one of the ponds to find out how deep the footprints were. The memory made him smile, although he was not in any smiling mood. He could still feel the shuddering sensation that killing left behind it. Did the Black Prince feel it too, even after all these years?

Morning came hesitantly, like ink mingling with milk, and Mo couldn’t say how long he had been sitting there, waiting for Fenoglio’s world to tell him what ought to be done next, when a familiar voice quietly spoke his name.

‘You shouldn’t be here on your own,’ said Meggie, sitting down beside him on the grass. It was white with frost. ‘It’s dangerous to be so far away from the guards.’

‘What about you? I ought to be a stricter father, and forbid you to take a step outside the camp without me.’

She gave him an understanding smile and wrapped her arms around her knees. ‘Nonsense. I always have a knife with me. Farid taught me how to use it.’ She looked so grown-up. He was a fool, still wanting to protect her.

‘Have you made it up with Resa?’

Her anxious expression made him feel awkward. Sometimes it had been so much easier to be alone with her.

‘Yes, of course.’ He put out a finger, and one of the dragonflies settled on it. It looked as if it were made of blue-green glass.

‘And?’ Meggie looked inquiringly at him. ‘She asked them both, didn’t she? Fenoglio and Orpheus.’

‘Yes. But she says she didn’t come to an agreement with either of them.’ The dragonfly arched its slender body. It was covered with tiny scales.

‘Of course not. What did she expect? Fenoglio isn’t writing any more, and Orpheus is expensive.’ Meggie frowned.

He stroked it with a smile. ‘Watch out, or those lines will stay, and it’s rather too early for that, don’t you think?’ How he loved her face. He loved it so much. And he wanted it to look happy. There was nothing in the world he wanted more.

‘Tell me one thing, Meggie. Be honest with me – perfectly honest.’ She was a far better liar than he was. ‘Do you want to go back too?’

She bent her head and tucked her smooth hair back behind her ears.

‘Meggie?’

She still didn’t look at him.

‘I don’t know,’ she said at last, quietly. ‘Maybe. It’s a strain, feeling afraid so often. Afraid for you and Resa, afraid for Farid, for the Black Prince and Battista, for the Strong Man …’ She raised her head and looked at him. ‘You know Fenoglio likes sad stories. Maybe that’s where all the unhappiness comes from. It’s just that sort of story …’

That sort of story, yes. But who was telling it? Not Fenoglio. Mo looked at the frost on his fingers. Cold and white. Like the White

Women … sometimes he woke from sleep with a start because he thought he heard them whispering. Sometimes he still felt their cold fingers on his heart, and sometimes – yes – sometimes he almost wanted to see them again.

He looked up at the trees, away from all the whiteness below. The sun was breaking through the morning mist, and the last few leaves shone pale gold on branches that were now almost bare. ‘What about Farid? Isn’t he a reason to stay?’

Meggie lowered her head again. She was taking great care to sound casual. ‘Farid doesn’t mind whether I’m here or not. He thinks only of Dustfinger. It’s been even worse since he died.’

Poor Meggie. She’d fallen in love with the wrong boy. But when did love ever bother about that?

She tried very hard to hide her sadness when she looked at him again. ‘What do you think, Mo? Is Elinor missing us?’

‘You and your mother certainly. I’m not so sure about me.’ He imitated Elinor’s voice. ‘Mortimer! You’ve put that Dickens back in the wrong place. And why do I have to tell a bookbinder not to eat jam sandwiches in a library?’

Meggie laughed. Well, that was something. It was getting harder every day to make her laugh. But next moment her face was grave again. ‘I do miss Elinor very much. I miss her house, and the library, and the café by

Inkdeath

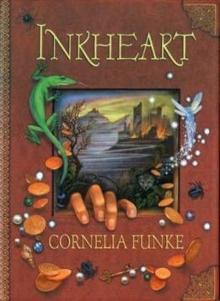

Inkdeath Inkheart

Inkheart Ghost Knight

Ghost Knight Inkspell

Inkspell The Golden Yarn

The Golden Yarn Fearless

Fearless The Thief Lord

The Thief Lord The Griffin's Feather

The Griffin's Feather Igraine the Brave

Igraine the Brave Reckless

Reckless When Santa Fell to Earth

When Santa Fell to Earth Dragon Rider

Dragon Rider Living Shadows

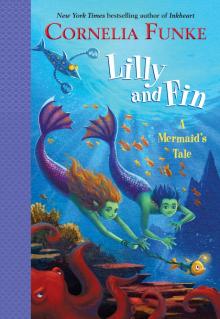

Living Shadows Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale

Lilly and Fin: A Mermaid's Tale The MirrorWorld Anthology

The MirrorWorld Anthology The Glass of Lead and Gold

The Glass of Lead and Gold Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Incredibly Revolting Ghost Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness!

Ghosthunters and the Totally Moldy Baroness! Reckless II

Reckless II Griffin's Feather

Griffin's Feather Emma and the Blue Genie

Emma and the Blue Genie Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost

Ghosthunters and the Gruesome Invincible Lightning Ghost Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom!

Ghosthunters and the Muddy Monster of Doom! Inkheart ti-1

Inkheart ti-1 The Pirate Pig

The Pirate Pig Inkspell ti-2

Inkspell ti-2 The Petrified Flesh

The Petrified Flesh Inkdeath ti-3

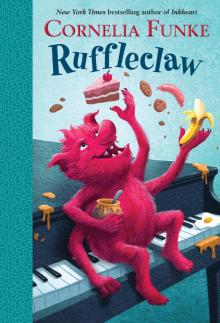

Inkdeath ti-3 Ruffleclaw

Ruffleclaw Lilly and Fin

Lilly and Fin